“Fat is wrong, and you don’t belong.”

Before I discovered the empowering body positivity movement, those were the haunting words I often repeated to myself, echoing the cruel laughter from my grade school cafeteria and the judgmental comments from neighborhood kids. I vividly recall the mornings spent sitting in front of the mirror, dreading the ride to the drop-off line at Randolph Park Elementary. It baffled me why my mere existence would provoke disgusted looks from classmates, who would scoot their lunch trays away from mine and mutter the word “ew” at the slightest accidental touch. I felt like an outcast, an unwelcome presence in a world where I simply wanted to belong.

When they weren’t laughing, they resorted to more subtle forms of bullying, like pointing fingers and kicking my chair, accompanied by that infuriating “so what” smirk whenever I shot them a fierce glare. It was as if my size was contagious, something vile, something illegal. I was the sensitive, soft-spoken, big, *DARK-SKINNED* girl who was too timid to defend herself, and they fully recognized that. All I could do was fight back tears, questioning what I could have possibly done to deserve such treatment… simply for existing.

This negativity forced me to hide my authentic self for many years, leading me to dim my natural shine. I overcompensated with humor born from trauma, adopting roles just to be seen and heard beyond the comfort of my loving family. Coming from a Southern household—filled with cornbread, collard greens, and warm hugs—I was fortunate not to experience the tales of a miserable Grandma Gretchen or an Auntie Anne who fat-shamed family members at holiday dinners, scrutinizing their plates and commenting on their size.

My mother was a constant source of encouragement, frequently reminding me of my beauty, and her confidence as a fellow plus-size woman was truly inspiring. Despite her affectionate kisses on my chubby, little chocolate cheeks and her heartfelt compliments about how precious her baby girl was, I struggled to internalize those affirmations. Her high self-esteem didn’t transfer to me; despite her reassurances, if I didn’t feel beautiful, her words fell flat. The reality was that the world around me made my obesity a social crime, a stigma that haunted me, at least in their eyes. I longed to fit in without the harsh ridicule associated with taking up space or being seen as too much for the in-crowd.

In the mid-to-late 2000s, my mother made the decision to remove me from public school during my fourth-grade year, opting to homeschool my older sister and me. The relentless bullying and toxic environment left her with no option. Homeschooling granted me the time to explore the then-burgeoning internet and the world of social media. This was a transformative experience. I began creating safe spaces through virtual friendships based on shared interests. Online, people appreciated me for who I was; they uplifted my spirits, allowing me to embrace the boisterous, outgoing, and vibrant person I had always wanted to be but felt too afraid to express in the real world.

Suddenly, the popularity I had yearned for during my childhood became my escape during my pre-teen and teenage years, filled with fan-girl forums dedicated to my favorite boy bands. Within these digital communities, my weight was irrelevant, as members only knew me through my username or a carefully curated avatar of my face, often edited to present the best version of myself, from the neck up.

Then, one day, while navigating the vast online world, I stumbled upon the now-controversial #bodypositivity movement. This discovery marked a pivotal shift in my perspective.

Unveiling My Journey into the Body Positivity Movement: Understanding Its Origins and Impact

My journey into the realm of body positivity began in the 2010s, as I found myself nestled in my all-pink bedroom, scrolling through what was then called Twitter (now X) and Instagram. What had once served as armor against shame transformed into a powerful statement of empowerment. To be fat, to be free, to embrace every aspect of myself that I had been told to hide—this realization felt exhilarating. Finally, I could stop concealing my authentic self behind filters and selective photos. I discovered a community of girls and women who looked like me, boldly owning their bodies and everything that came with them.

While I can’t pinpoint the exact year, the era of 2013/2014 stands out vividly in my mind. I remember the excitement it sparked within me, marveling at the unapologetic liberation displayed by numerous full-figured women, a representation that had previously been absent. Sure, there had been icons like actress/comedienne Mo’Nique and model Toccara Jones leading the charge for The Curvy Committee during the Y2K era, particularly in entertainment, but this new trend featured everyday individuals breaking into uncharted territory with nothing but a hashtag and genuine bodies. Their confidence resonated with the average person who couldn’t afford fancy outfits or the luxury of being deemed conventionally attractive.

Prior to diving deeper, let’s clarify: what is body positivity, and what are its roots?

According to Verywell Mind, body positivity refers to the belief that every individual deserves a positive body image, irrespective of societal standards regarding ideal shape, size, and appearance. Psychology Today offers another definition, describing it as an effort to accept bodies of all sizes and types rather than conforming to prevailing beauty ideals.

However, it’s crucial to recognize that while modern interpretations seek inclusivity within the body positivity movement, its origins trace back to fat activism. Following the Victorian dress reform movement against restrictive garments for women in the 1800s, the late radio personality Steve Post is credited with jumpstarting this coalition when he organized a significant “Fat-in” event in New York City’s Central Park in 1967. This transformative gathering, which attracted hundreds, was covered by The New York Times in an article entitled “Curves Have Their Day in Park; 500 at a Fat-in Call for Obesity.”

Published on June 5 of that year, the article detailed how “short fat people, tall fat people and dozens of slim individuals who wished they were fat, gathered in Central Park yesterday afternoon to celebrate human obesity.”

The Times further reported that attendees carried banners emblazoned with slogans like “Fat Power,” “Think Fat,” and “Buddha Was Fat,” wore buttons proclaiming “Help Cure Emaciation, Take A Fat Girl to Dinner,” and conducted anti-slim rituals that included burning diet books and a large photograph of Twiggy, the iconic skinny model, while stabbing a cold watermelon.

At that time, Steve Post was a 23-year-old chief announcer for WBAI-FM, who had recently gained weight and organized the “Fat-in” to protest discrimination against larger individuals. He expressed to the publication, “Advertising campaigns have made us feel guilty about our size.”

Post was adamant that “People should be proud of being fat. We want to show we feel happy, not guilty. That’s why we’re here.”

His advocacy inspired writer Lew Louderback to write an influential essay titled “More People Should Be Fat” for the Saturday Evening Post, which pushed back against the social stigma surrounding plus-size individuals. This essay ultimately led engineer Bill Fabrey to establish the National Association to Advance Fat Acceptance in 1969. According to their website, the NAAFA (formerly known as the National Association to Aid Fat Americans) is a non-profit organization dedicated to protecting the rights and improving the quality of life for larger individuals.

By the 1970s, California feminists who were also distressed by the prejudice faced by the plump began the Fat Underground. A 1998 article in Radiance Magazine Online noted that this group “asserted that American culture fears fat because it fears powerful women, particularly their sensuality and sexuality.” They employed bold rhetoric, claiming “Doctors are the enemy. Weight loss is genocide.” Although mainstream sympathetic academics urged them to temper their language, many ultimately adopted much of the Fat Underground’s foundational arguments.

Fast forward to the 1990s, where anti-fat commercials, diet programs, and restrictive beauty standards began to overshadow the decades-long efforts aimed at dismantling skinny bias. This wave continued into the 2000s, where sizes as low as 8 were labeled “plus size,” and women were pressured to conform to the physical ideals set by video vixens and magazine models. However, a new dawn emerged in the 2010s, birthing what we now recognize as the body positivity movement.

The Evolution of the Body Positivity Movement: Its Impact on My Life and Others

Throughout my formative years, I loathed the excess fat behind my neck, often referred to as a buffalo hump, because it made sleeping on my back uncomfortable and rendered me incapable of taking flattering photos in strapless outfits. I consistently felt awkwardly shaped—my breasts larger than those of my peers while my stomach hung over my pants. To add insult to injury, my legs were slender, creating an uneven, top-heavy silhouette.

In a time when healthy bottoms were celebrated, I grappled with feelings of inadequacy regarding my body—both from others and within myself. I envied those, like my sister, who boasted a pear-shaped figure—small-chested with wide hips and curves too lovely to be concealed. The celebrity women who epitomized plus-size beauty didn’t resemble me, keeping me trapped in a loop of wishing to look like the ones everyone admired. My apple-shaped body was simply not socially acceptable.

The rise of the body positivity movement on social media redefined not only cultural standards but also my perception of my body. Yes, with all its unique features, extra layers of love, and shea-buttered rolls, I learned that my perceived flaws did not diminish my humanity. I was just as valid as those who flaunted their “fit” bodies, as if my weight automatically indicated poor health. With various brands and mainstream figures joining the movement, body positivity evolved into a global phenomenon before my eyes. Influencers on platforms like YouTube were sharing fashion tips for voluptuous women, and corporations began expanding their size ranges. Embracing oneself became a focal point of this time. What an incredible era to be alive.

Then came Tess Holliday with her powerful declaration, “EFF YOUR BEAUTY STANDARDS.” This campaign, launched in 2013, strategically challenged societal norms around beauty, fostering connections among those who defied the status quo and promoting diversity. Holliday, a prominent figure in the plus-size community, reshaped the narrative, demonstrating that modeling and worth are not defined by weight. Her bold approach has undeniably propelled the progress of fat fashion over the past decade, increasing visibility for larger bodies in numerous marketing strategies.

However, it’s essential to note that Holliday’s emergence sparked controversy, as critics accused her and others of promoting a “harmful,” pro-obesity message. This leads me to ask: When did it become dangerous to love oneself? Are we not allowed to embrace our identities simply because of our size?

As the face of numerous prominent clothing lines such as Torrid, H&M, and ELLE, Tess Holliday has certainly opened countless doors for future generations. As influencers gained popularity on X (formerly Twitter) and Instagram, various body types received the spotlight, empowering women like me to pursue lives free from the limitations imposed by unsolicited societal advice. I never anticipated that engaging in a Twitter thread would lead to my own taste of the body positivity movement.

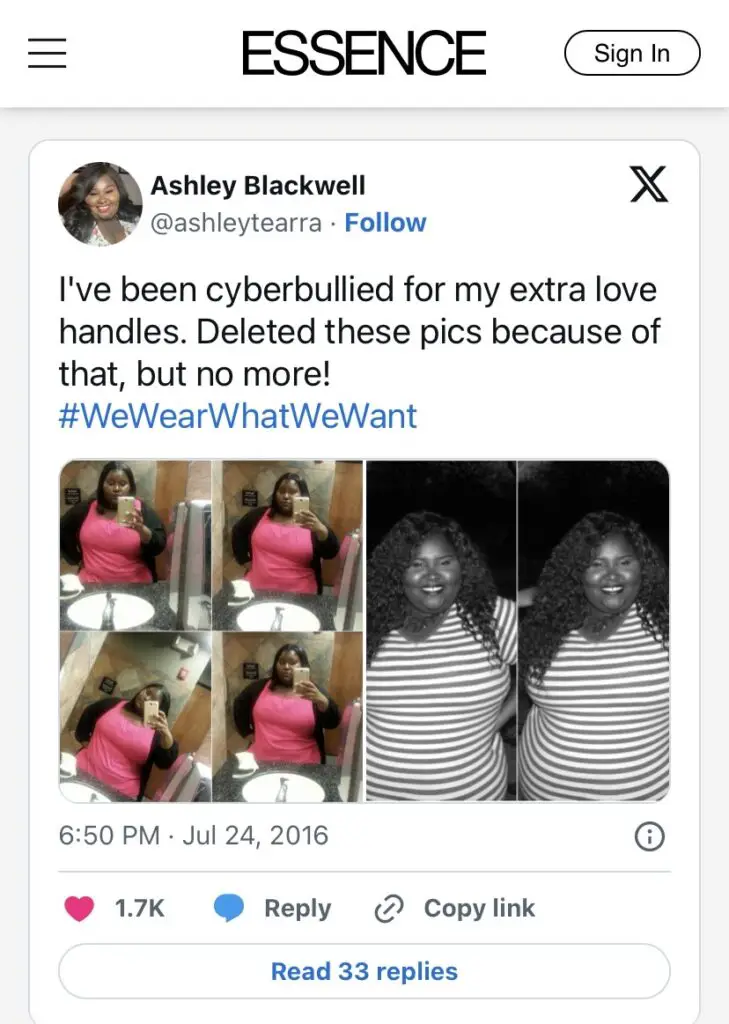

In 2016, internet personality Simone Mariposa launched the #WeWearWhatWeWant hashtag, encouraging plus-size women to showcase themselves in whatever made them feel comfortable in response to the rampant body-shaming from those of us who wore extended sizes. My post featuring me in a vibrant pink outfit with bold stripes garnered hundreds of likes and replies, even leading to an interview offer from Today.com and mentions in Essence and Buzzfeed. While the flood of attention offered a glimpse of “fifteen minutes of fame,” the accompanying negativity overshadowed the support. I found myself contemplating deleting the post as tears streamed down my face, feeling like that little girl again, desperately seeking normalcy.

The harsh comments labeling me as everything from “smelly” to “monkeys” pierced through my self-love journey, threatening to derail the progress I had made since childhood. It felt like an insurmountable obstacle, casting a shadow over my hard-earned confidence, even if just for a fleeting moment.

But I persevered.

Gradually, the noise faded, and the hurtful jokes became less impactful. I began to celebrate myself for all that I was and all I would become. This experience ignited my passion for advocating for plus-size representation. Whether through social media posts or discussions with close friends, I’ve never shied away from my belief: fat people matter, too. Especially women. I won’t shy away from saying that we feel the effects of fatphobia the hardest, and it’s disheartening. Sometimes, this negativity even comes from within our circles. But that’s a conversation for another time, so I’ll leave it here.

Through initiatives like the body positivity movement, we have managed to challenge the countless stigmas and stereotypes imposed upon us, advocating for clothing brands to cater to more than just one body type. While I believe plus-size fashion has made significant strides, there is still much work to be done. Companies that claim to “cater to the curvy” must recognize that offering a 2X or 3X size does not equate to true inclusivity. That is an undeniable reality.

Although once a vibrant sector for individuals of all sizes, some would argue that body positivity is no longer as prominent as it once was, particularly with the expanding definitions of who fits under its umbrella and the criticisms labeling it as “toxic.” Additionally, while some claim it endangers American health, others assert that the community promotes forced positivity. In a 2022 episode of The Feisty Women’s Performance Podcast, fat cyclist Marley Blonsky remarked, “Body positivity is merely being overwhelmingly positive about our bodies, and I just don’t think that’s realistic.”

She elaborated, “I encounter daily frustrations with my body, whether it’s my knee or my hair. Accepting the parts I don’t love, like my troublesome knee post-surgery, doesn’t require me to love them. I think there’s a substantial body positivity movement, but it often pushes an unrealistic narrative of ‘I love my rolls. I love my cellulite.’ But why should we feel obligated to love every part of our body?”

Blonsky then explained why she finds body neutrality more beneficial: “Being neutral about your body means acknowledging both the good and bad aspects and being grateful for what your body does for you,” ultimately concluding, “My positive feelings about my body won’t change the reality of airplane seat sizes or the judgment I face from the doctor regarding my knee issues.”

In summary, while opinions vary, I believe it would be unwise to downplay the impact of the body positivity movement on girls like me, who lacked spaces to celebrate the beauty of their bodies. We have fought for the freedom to say: “This is who I am, and I love who I am.” It’s important to acknowledge that not every day will be perfect, and no, you won’t love every part of yourself. However, body positivity transcends mere surface-level appreciation; it’s about allowing yourself to live, laugh, and cherish your existence, even on the tough days—because you absolutely deserve that right.

It’s about providing a platform for marginalized individuals, opening doors to confidence-building opportunities for those who may not have had the courage to step into the spotlight or stand before the camera. Far too often, especially as plus-size women, we feel pressured to conform to societal standards, believing we can only smile when our bodies fit a narrow definition of beauty. But the reality is, it’s in those moments of self-acceptance, where we appreciate ourselves as we are rather than fixating on who we aspire to be, that we uncover the most exquisite facets of our true selves.

For many, this journey unfolds through cherished relationships, personal attributes, or even something as simple as the clothes they wear. Through platforms like The Curvy Fashionista, our message cuts through the backlash against the erasure of larger individuals’ rights and feelings, providing a prominent space for bodies that are no longer concealed behind quick-fix diets or extreme measures.

No more hiding. What you see… is what you will get.

Here you can find the original article; the photos and images used in our article also come from this source. We are not their authors; they have been used solely for informational purposes with proper attribution to their original source.