In 1979, Universal Studios released a quasi-remake of 1931’s Dracula, the century’s pre-eminent vampire film. Like Tod Browning’s classic, director John Badham and screenwriter W. D. Richter adapt a revival of the hit 1920s stage play, this time with Frank Langella stepping into the iconic cloak and fangs. Yet this Dracula, tantalizingly taglined with “a love story,” divorces itself from its origins while also reverting to the ominous essence powering Bela Lugosi’s film — and Bram Stoker‘s novel — after decades of B-movie imitations.

In fact, Badham’s effort beat Francis Ford Coppola‘s Bram Stoker’s Dracula to the punch as the first mainstream adaptation to catapult the tale’s sensual implications into an explicit Gothic romance that embraced the genre’s morally dubious eroticism. (Technically, Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre remake beat it to the punch, but Badham’s Dracula is the first official adaptation to make the move.) Yet this atmospheric, entertaining, and quite sexy interpretation breezed past audiences’ radar into relative obscurity. It’s a shame, because its unique approach marks a cultural turning point in the Count’s image, for which this movie has never received enough credit.

What Distinguishes 1979’s ‘Dracula’ from Bela Lugosi’s 1931 Version?

The film follows the Lugosi classic in two broad strokes: condensing the book’s cast and including familiar quotes. Otherwise, it wastes no time simultaneously tapping into its text’s melancholic roots and swerving from them — with dramatic abandon, no less — by opening with a transport ship caught in a vicious storm. Most adaptations establish their suffocating mood through the Transylvanian-set prologue. Badham and Richter leave that necessity to the capsizing waves, the howling thunder, Dracula clawing the poor sailors to shreds, and John Williams‘ enticing yet menacing score.

Even the wildest deviations benefit Dracula‘s structure and goals. Mina Van Helsing’s (Jan Francis) — the doomed friend of Lucy Seward (Kate Nelligan) and the daughter of Professor Van Helsing (Laurence Olivier) — rescue of Dracula from the shipwreck eases the vampire into the play’s dialogue-heavy surroundings. Devoting extended time to the characters’ interactions also strengthens the evolution of Dracula and Lucy’s star-crossed, forbidden romance and substantiates the threat posed by the titular vampire.

How Does Frank Langella’s Performance Highlight Dracula’s Elegance and Vulnerability?

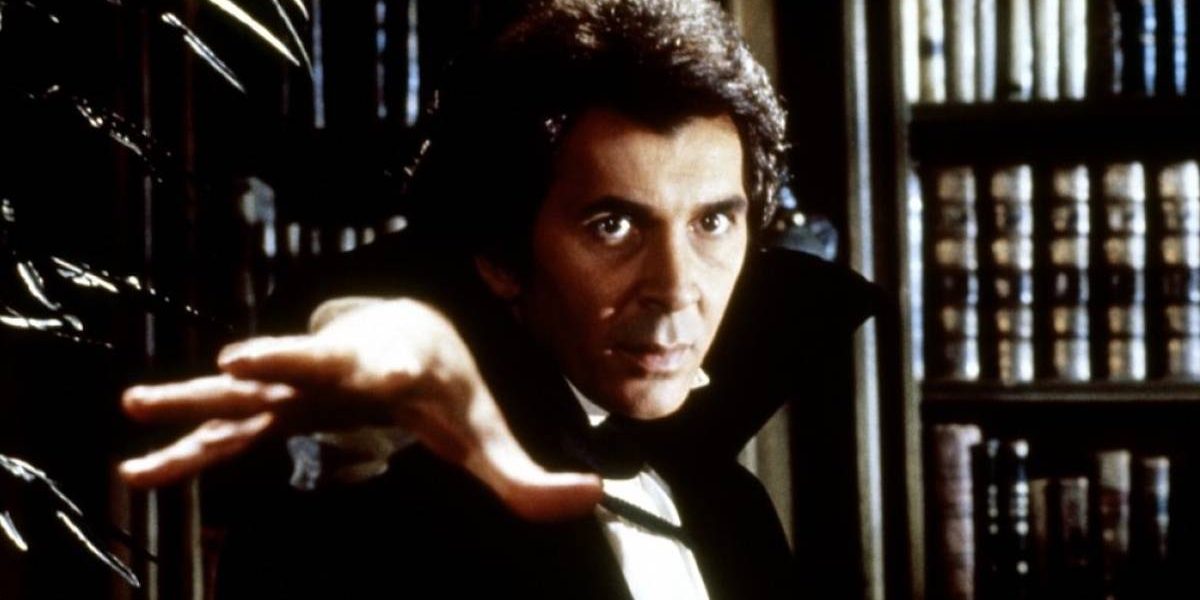

The accusations against Langella in 2022 are deeply upsetting for manifold reasons. In this case, it’s difficult to reconcile his legally-declared misconduct with the fact that he turned in a performance that deserves to be ranked among the Dracula greats. He differentiates his interpretation by playing the character as less monstrous. Make no mistake, this apex hunter’s irresistibly commanding predation remains intact; he repays Mina’s kindness by murdering her. When other mortals presume they can defeat him with religious iconography, his default civility drops into seething fury — a reaction born from Dracula’s narcissism more than feral instinct.

Likewise, Langella emphasizes the Count’s regal grace. Dracula kicks off his grand introduction scene by tossing off his cape in one accustomed movement, never glancing at the servant who takes the garment because he deems them inferior. Unlike Lugosi, this Dracula isn’t idiosyncratic; his effortlessly charming decorum fits right in with London society. A quote as famous as “I never drink wine” becomes a casual remark from a handsome nobleman no one could suspect of such heinous supernatural activity.

Strip away his sinister disaffection and courtly dignity, however, and an undercurrent of vulnerable weariness weighs down his sentiments that decree blood-sucking immortality as a fate “worse […] than death.” Dracula never waxes poetic about loss or solitude, but Langella injects mournful reserve into a creature who defies death and grasps its permanence. Lugosi praising “the children of the night” becomes Langella murmuring about “what sad music they make” in a pensive, bitter tone; this Dracula yearns for the sun’s warmth yet never doubts his right to rule the night. When it comes to Lucy, the “queen” he cherishes in his best approximation of love, Dracula’s amused intrigue morphs into an intimate and intensely tender sincerity. This Count doesn’t need hypnosis; he makes love through the gravitational force of his longing before his body follows suit.

How Did The 1979 ‘Dracula’ Establish Him as a Love Interest Before Vampire Romance Became Popular?

In short, Dracula is hot: an unambiguous sex symbol and a Byronic love interest who awakens Lucy’s darkest desires. Conveniently, Lucy happens to be all about that life. A self-assured woman who yields to no man, Lucy eschews the expectations surrounding sacrificial lambs and wilting damsels. She’s too busy securing her career and advocating for women’s rights to get married. As time wears on, it’s clear she’s surrounded by well-meaning but dismissive fools; Jonathan Harker (Trevor Eve) turns his jealous resentment upon her, while her father (Donald Pleasence) addresses Mina’s sudden death with blithe detachment. It’s obvious why Lucy would abandon Jonathan’s proffered domesticity for the enigmatic passion and invigorating freedom Dracula represents. Spirited and curious, Lucy challenges and matches Dracula as his equal. The vampire king must earn his bride, not claim her.

As for that dalliance, Badham’s sensual choices carry notes reminiscent of the female gaze: Lucy kissing him of her own enthusiastic volition, Dracula trailing his fingertips down the length of Lucy’s arm without touching her skin. Their consummation manifests as a surrealist love scene somewhere between a classic Harlequin novel and a James Bond opening credits sequence. Dracula, shirt half-undone, emerges from the swirling fog and sweeps Lucy into a reverential bridal carry before drinking her blood, with hallucinatory images overlaying their entwined silhouettes against a saturated red background.

To be fair, Lucy doesn’t consent to romancing a vampire. Assault metaphors are baked into Stoker’s work, but Lucy’s uncharacteristic silence about her beau’s undead sorcery turns her agency vague — an unfortunate move for an adaptation this revisionist. At least she doesn’t lose her fire; she spits fury at the men who literally hold her down and confine her behind locked doors. By the time Dracula “rescues” her with dashing aplomb, we’re rooting for these kids to run away together.

Why Is The 1979 ‘Dracula’ Adaptation Unfairly Overlooked?

Dracula‘s refusal to dampen its fantastical style compensates for its unintentionally cornball moments. Peter Murton‘s lavish production design creates a distinct sense of place, whether it’s the rain-drenched Whitby seaside or the haunting seductiveness of Dracula’s home — an ornate mansion where cobwebs drape down to the leaf-littered floor, gargoyle faces are carved into the staircase handrail, and candles proliferate every inch. Gilbert Taylor‘s cinematography embraces this visual feast through wide shots and sparse callbacks to Lugosi’s film while accommodating the romantic angle through strategic close-ups and symbolic framing. The then-elaborate, now-dated special effects achieve just enough impact while maintaining Edwardian costumes courtesy of designer Julie Harris, refreshing traditional Victorian aesthetics.

And yet, this summer horror flick debuted to positive-to-middling reviews and a chilly box office reception ($20 million). With all pieces in place for success, why didn’t it achieve widespread recognition? Since dissecting Universal’s marketing strategy isn’t possible, speculation suggests oversaturation may have played a role. Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre and Love at First Bite, both released several months earlier contributed to this situation. Between Herzog’s solemnity and Love at First Bite’s comedic slant—coupled with Christopher Lee’s extensive tenure at Hammer Films—the result likely dampened interest in yet another iteration of Dracula. Vampires continue to captivate our imagination but their popularity follows patterns of peaks and troughs over time. Unfortunately for this adaptation of Dracula, timing was not on its side — but its Gothic decadence remains glorious.

[nospin]Here you can find the original article which includes photos used in our article sourced from there as well.[nospin]