Being a musical genius often comes with the weight of being ensnared by your own extraordinary talent. This duality brings both accolades and challenges, especially for those hailing from marginalized communities.

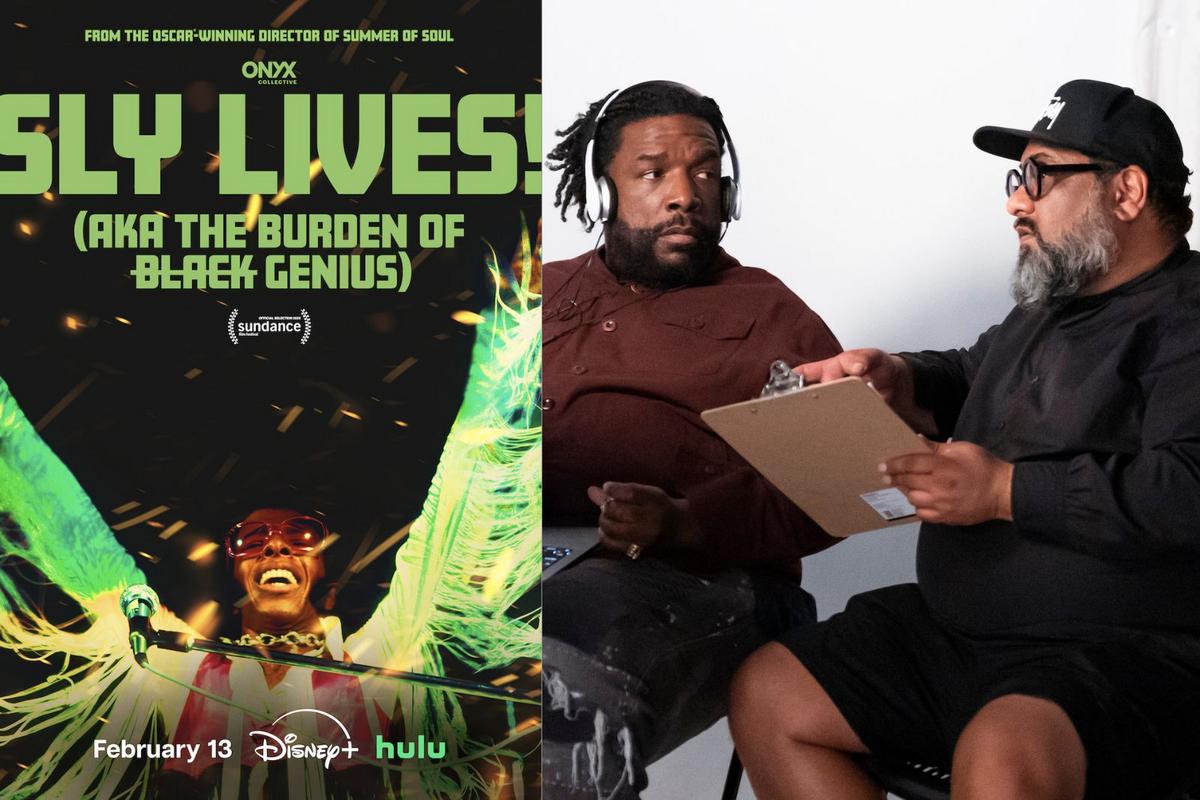

This theme is central to the documentary Sly Lives! (aka The Burden of Black Genius), directed by Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson and now streaming on Hulu. The film chronicles Sly Stone’s rise to fame and his significant contributions to popular music. However, it also delves deeply into the societal pressures he faced as a mixed-race, mixed-gender band leader, which made him a target for biased journalists and industry insiders. Sly Lives! explores how drug addiction impacted his life, career, and family, culminating from the relentless pressure to conform to a narrative he could never fit, along with the typical struggles associated with immense fame.

As Vernon Reid of Living Colour notes, the film encapsulates the enduring question that Black artists have grappled with for decades: who do you think you are? Questlove himself, who previously directed the Oscar-winning Summer of Soul, has also wrestled with this identity crisis throughout his own artistic journey.

Recently, UCR interviewed producer Joseph Patel, who collaborated with Questlove on Summer of Soul, to discuss the significance of Sly’s narrative and why it resonates today.

Questlove opens the film by proposing a thought-provoking theory: for many Black artists, the fear of success can be as daunting, if not more so, than the fear of failure. Sly Stone exemplified this struggle, as one of the first Black artists to confront it publicly. Can you expand on this idea and share your perspective on whether things have improved or worsened for Black artists in similar situations?

While this is primarily Ahmir’s insight, I’ve observed that he too experienced significant guilt after winning the Oscar for Summer of Soul. He wondered how his bandmates would perceive him afterward. This internal conflict has likely weighed heavily on his mind. My close friendship and collaboration with Questlove have allowed me to grasp this concept and incorporate it into Sly Stone’s narrative. Questlove theorizes that Sly represents the first artist in the post-Civil Rights Era who equally catered to both Black and white audiences, which must have been an overwhelming responsibility. Just think about being 26, a Black artist leading a genre-blending rock band, headlining Woodstock, and gracing the cover of Rolling Stone, all while attempting to bridge racial divides through music. He faced uncharted pressures with no template to emulate; thus, this film not only tells Sly’s story but also highlights the weight of success borne by Black artists in America.

Indeed, the film profoundly addresses the intersectionality of race and gender in the arts and critiques how the music industry handles drug addiction. It opens up broader dialogues. Could you elaborate on this?

Towards the film’s conclusion, Sly discusses his experiences in rehab, touching on trauma and the complexities of generational trauma that remain largely unspoken. He conveys feelings of events that may have impacted him deeply yet are now obscured from memory, which was a powerful moment for us. It’s startling to recognize that he lacked the vocabulary to articulate his plight. Back in the ’80s, rehab and therapy were still shrouded in stigma, exacerbating the challenges he faced.

Exactly. The film also emphasizes how drug addiction was often perceived as a personal failing, rather than an issue influenced by external circumstances. During those years, Sly was rarely asked about the underlying causes of his struggles; instead, the focus was on why he was engaging in such behavior.

Absolutely. We aimed to portray Sly’s story with empathy, acknowledging that the immense pressures and anxieties he faced may have contributed to his attempts to escape reality. As Chaka Kahn aptly puts it, cocaine can provide a false sense of security when everything is actually falling apart. However, we also wanted to ensure that Sly retained agency in his narrative, striking a delicate balance between empathy and accountability.

You?ve discussed why Sly himself did not participate in the film’s production. He achieved sobriety a few years ago around the time of Summer of Soul. You mentioned, “He can’t speak in full sentences. His eyes reveal a precociousness and a lucidity that’s there, but his motor function doesn?t exist.” This notion resonates with me, especially as I run a podcast about Joni Mitchell, who also exhibits this clarity yet struggles to express herself in conventional ways. What are your thoughts on making a documentary about someone who is both present and absent in this way? What challenges does this present?

It certainly presents unique challenges. We faced a choice: should we include him, potentially undermining the empathy we aimed to convey in his story? Sly’s historical significance aligns with a time when media was rapidly evolving, so we had access to ample archival interviews that allowed us to capture his voice. Yet, it also created a creative opportunity. Even if we had secured a camera interview with Sly, it?s unlikely we could have elicited the kind of reflective dialogue about pivotal moments in his career that we desired. Most artists are not inclined to reveal those vulnerabilities. However, we could engage other artists like D’Angelo and Chaka Kahn, who have faced similar challenges. Their insights serve as both reflections on Sly’s journey and their own experiences, adding depth to the storytelling and distinguishing our approach from more traditional music documentaries. We prioritized speaking with those who have truly experienced the struggles we explore.

Watch the Trailer for ‘Sly Lives! (aka The Burden of Black Genius)’

Another critical aspect of the film examines how Sly’s musical evolution mirrored the cultural shifts from the ’60s to the ’70s, particularly during the “There’s a Riot Going On” period. Q Tip points out that while a white artist like David Bowie underwent stylistic transformations and received widespread acclaim, Sly faced criticism and was often confined to a singular identity.

Indeed, once Sly began to explore different musical directions, critics described him using derogatory terms such as “pimp’s wisdom” and “gangster looks.” The language used to portray him was deeply problematic. This narrative focuses specifically on a Black artist and the associated burdens, yet the film’s artwork features the word “Black” crossed out. This symbolizes our intention to present a broader perspective; while Ahmir’s perspective centers on Black genius, the theme of the burdens that accompany success is universally applicable. For instance, Fiona Apple, a close friend of Ahmir, has faced similar challenges, experiencing harsh treatment in the industry despite her early success. Our aim was to highlight that these struggles transcend race and gender, resonating across all levels of creative achievement.

What has been the most surprising or insightful discovery you made about Sly during this filmmaking process?

I was particularly astonished to learn that he produced the Great Society’s “Somebody to Love,” a significant song that later became Jefferson Airplane’s anthem. This track embodies the spirit of the psychedelic era, and I had no prior knowledge of Sly’s involvement in its production. Furthermore, there are studio session sheets revealing that he produced work for the Warlocks, who later became the Grateful Dead. His diverse ability to produce music across genres, from white rock bands to R&B, was a revelation to me and left me in awe from a music enthusiast’s perspective.

Listen to the Great Society’s ‘Somebody to Love’

What key message do you hope viewers will take away from this documentary?

Our hope is that audiences come away from the film with a renewed sense of responsibility towards the artists who enrich our lives. It is vital to extend empathy and grace to them, allowing for their humanity to shine through. Ahmir and I emphasized from the outset that we wanted to encourage viewers to refrain from imposing unrealistic expectations on artists, permitting them the space to experiment without facing ridicule or pressure. Ultimately, we aspire for people to foster a sense of compassion and understanding towards these creators, recognizing that their artistic expressions represent profound human experiences rather than mere commodities.

Discover the Impactful Albums of Sly and the Family Stone

Through their innovative, radio-friendly soul-pop sound in the early ’70s, Sly and the Family Stone emerged as one of the most influential groups of the era.

Gallery Credit: Michael Gallucci