Charlie Peacock, a name that evokes curiosity, seems more suited for a pop celebrity than a behind-the-scenes luminary known for his impactful work as a producer, songwriter, and record label owner. He did achieve a level of cult status as a singer-songwriter during the 1980s, particularly in circles of progressive Christian music enthusiasts who yearned to see spiritually-inclined artists breaking into the alternative rock scene. Yet, beyond this niche audience that likely still cherishes him as a star, he never attained widespread fame ? a fact humorously encapsulated by his daughter?s remark that he was ?just well-known,? a quip that Peacock (born Charlie Ashworth) found amusing enough to repeat in his latest book.

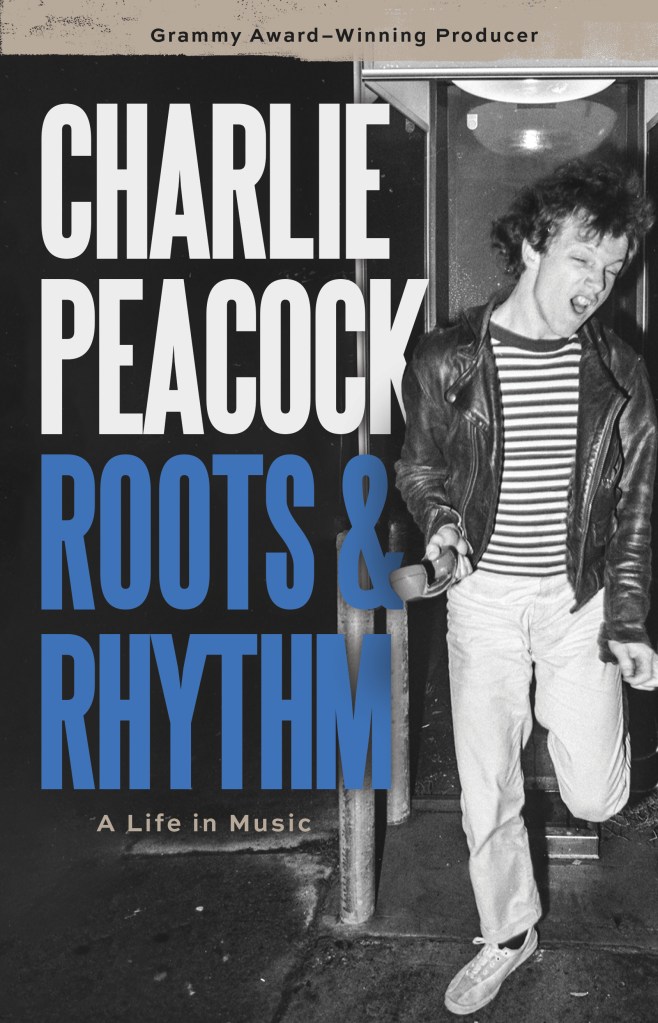

His memoir, titled ?Roots and Rhythm: A Life in Music,? is a treasure trove of anecdotes from his 1980s journey with renowned labels like Island, A&M, and the alternative Christian label Exit Records. It paints a picture of a career that has taken unexpected turns ? from being a leading light in the Sacramento rock scene to becoming a Nashville-based pop hitmaker with Amy Grant?s ?Every Heartbeat.? The narrative also highlights his efforts in founding the Re:suppose label and nurturing artists such as Switchfoot. His most significant commercial success emerged as the producer of the Civil Wars? acclaimed albums. Adding another layer to his multifaceted career, he ventured into the world of jazz, producing a top 10 jazz album while collaborating with notable musicians like John Patitucci, all while grappling with a debilitating neurological disorder.

As readers might expect from Peacock?s writing style, this memoir transcends a mere career retrospective; it serves as a spiritual exploration. It delves into themes of geography, ancestry, and his admiration for literary and musical giants like Kerouac, Coltrane, and Jesus ? not necessarily in equal measure, but in a way that resonates deeply within the rock ?n? roll narrative. ?Roots and Rhythm? offers a satisfying read for those curious about the inner workings of the music industry, as well as those seeking broader insights into life?s intricate tapestry ? although these themes may not always coexist within the same chapter. Variety had the opportunity to converse with Peacock on the day his Eerdmans book officially hit bookstore shelves.

Having released two books within a year ? one co-authored with your wife (2024?s ?Why Everything That Doesn?t Matter, Matters So Much: The Way of Love in a World of Harm?,? with Andi Ashworth), and the other being this memoir ? how did you manage to write them? It?s evident that this memoir required careful writing and thought, indicating it must have taken years to complete.

Absolutely. I was just discussing with Andi recently about the timeline, and we both recalled that I initially started this memoir 15 years ago. It coincided with our time back in Northern California, where we had a home for a while to spend time with my mother and family. During that period, I felt compelled to begin writing, intrigued by the power of place and the desire to reflect on my upbringing in the Yuba City farming community of the 1950s and 60s, and how that experience shaped who I am today. I also explored my proximity to San Francisco and the influences that shaped my eclectic musical tastes, particularly the legendary Bill Graham and his unique approach to concert programming, which brought together a diverse range of musicians like Jefferson Airplane and Albert King sharing the same stage as Miles Davis.

Your book seems to encompass multiple narratives. It appears you could have easily written separate books focusing solely on your family roots, insights into the music business, the CCM industry, or even your philosophical musings. Readers will approach this book for various reasons: some may seek your spiritual insights, while others may be drawn to your music industry experiences?

?I want to know who was in the room? ? yes, indeed. I can share this safely since you?re a journalist, and you?d never report it, but I actually began this memoir as an exploration of epistemology.

That?s a rather intriguing secret to reveal.

For me, it was about how I come to know what I know. In the process of writing, I discovered that a narrative approach, where I could weave these threads together, was most effective for me. Time and again, I found profound connections between stories that, to a first-time reader, might seem disjointed. However, for me, they became intricately linked, leading me to realize that this would be the guiding principle of the book?s structure.

A memoir that skillfully navigates time and themes can enrich the reader?s experience by revealing unexpected connections while maintaining a dynamic narrative flow, rather than presenting 30 pages dedicated to a single topic or time frame.

Precisely. Like you, I?ve read over a hundred music biographies and autobiographies, and the ones I cherish the most, such as Elvis Costello?s and Dylan?s ?Chronicles,? exemplify this approach. One of the challenges I faced ? and continue to face in my music career ? is being recognized as a writer rather than just a musician with a story to tell. I wanted this book to feel like a piece of art, rather than merely a byproduct of my music career. That desire fueled my creative process throughout.

Throughout the 15 years you worked on this memoir, did you discover any new themes or ideas that evolved beyond your initial drafts?

The themes of interconnectedness and the importance of place were present from the outset. However, I think a significant tension emerged for me: to be in the music business, one must also be in the name-making business. Yet, being in that business can be incredibly soul-crushing. I wanted to grapple with the experience of being someone who is not widely known, as encapsulated by my daughter?s observation in the book that I am ?just well-known.? I wanted to share my experiences as a largely behind-the-scenes individual whose solo career didn?t extend beyond college radio and Christian music. The memoir reflects on the challenge of navigating the music industry while observing how much fame influences opportunities, often overshadowing true talent or the quality of one?s work. This concept became a recurring theme throughout the book, illustrating the tension of watching others rise and fall, the constant need to prove oneself ? a relentless cycle in the music business that never truly ends.

In your book, you state: ?Name-making is among the top five most exhausting and inhuman endeavors.? However, it may be challenging to convince a 21-year-old reader in 2025 that they shouldn?t focus on name-making when everyone around them is preoccupied with impressions.

Indeed, Andi and I had a conversation about the concept of impressions over dinner recently, reflecting on when we first encountered that term. Many exceptional artists have been signed based on a gut feeling rather than metrics. It?s these heroes who emerge from obscurity, often making instinctual decisions about talent ? ?I see something in you and I can envision our collaboration lasting for decades.? It?s astonishing how absurd this notion sounds in the current metrics-driven landscape.

In one section of the book, you outline key transitional moments in your career, highlighting periods of success followed by realizations that certain paths were stifling. This includes your departure from the church-related scene in Sacramento, your involvement with Exit Records, and your transition to Nashville, where you worked largely behind the scenes in the CCM world for a decade. You eventually established your own label, only to sell it and pivot to support different types of artists. Jazz also emerged as a significant interest, leading to a top 5 album on the traditional jazz charts. Was it always clear when to make the decision that something wasn?t working for you anymore?

I think I touched on that in my writing about the influence of the Beats on me as a teenager, as well as my background in the West and migrant culture. I embody a sense of individualism and a rebellion against the status quo. However, I also have a friendly disposition; I enjoy collaborating and connecting with others. There?s always been this tension where, at some point, I realize, ?The freedom isn?t here anymore; it?s somewhere else.? My early influences and family narratives linger powerfully. The jazz aspect also plays a role: If I find myself in an environment where improvisation is restricted, I feel compelled to leave, as I deeply value risk and surprise in music.

The memoir opens with a dramatic moment ? the breakup of the Civil Wars, during a career peak as their producer. This serves as a metaphor for the many reversals of fortune that can occur throughout a career, particularly in a journey like yours.

Many younger readers may not have faced the other side of the mountain yet, but they will eventually find themselves in a position where they may be successful, perhaps even wealthy, only to realize that people have moved on. They might wonder: What is my worth now? Can I change perceptions about who I am? Can I make the phone ring again and gain attention from agents? Whether it’s seasoned professionals like T Bone Burnett or myself, the desire to reinvent oneself is crucial. You continuously strive to prove your worth and demonstrate your capabilities. This exhausting pursuit often focuses too much on the self, whereas ideally, as we grow older, we should shift our focus outward ? prioritizing building others up rather than seeking personal validation. Yet, in every field, we struggle with this, as there are always talented individuals emerging behind us, vying for our opportunities.

To what extent do luck and inherent adaptability play a role in survival, or are there individuals who are simply hardwired to adjust at the right moments?

In the book, I talk about hyper-vigilance and resilience. While I can?t speak for everyone, these traits have certainly played a role in my journey, helping me navigate through challenges, even when I felt broken and weak. At one point, I took a childhood PTSD assessment and scored a 6 on incidents from my past. In contrast, I scored a 10 on resilience. When I fell ill a few years ago and visited the Mayo Clinic, the doctor explained that my prolonged resilience is why it took so long for me to break down. This realization helped me acknowledge that I had cultivated a capacity to endure pain, whether physical or emotional, and that this endurance was critical in maintaining my music career.

Being honest, I have faced numerous tearful moments, grappling with the absurdity of my circumstances. Yet, the following morning, I?d remind myself that it?s just the way things are, and I must press on. There was a time when I turned to substance abuse as a coping mechanism. Anyone familiar with 12-step programs can attest to the series of cyclical incidents that arise from that path. Eventually, I realized that was not the solution; I needed to find a way to commit to my work, ensuring I excelled in writing songs, producing records, and delivering quality work on time. This required a level of dedication that allowed me to prioritize the essentials, enabling me to nurture the magical improvisation within music and dream big without constantly relying on others? financial support.

Charlie Peacock

Jeremy Cowart

As you mention in your book ? or your daughter does ? you?re not famous per se, ?just well-known.? Has it ever been challenging to let go of the dream of being a pop star, or did you transition to a behind-the-scenes role gracefully?

I wouldn?t say it was a seamless transition; I?d be lying if I didn?t admit to some confusion and jealousy. However, I?m quite analytical, and I quickly realized that if artist A excelled in the public-facing role, whether due to their musical choices or entertainment persona, then a blend of my talents with theirs would yield a better outcome. This realization helped me understand my purpose: to contribute my unique touch to projects rather than being the sole focus.

Ironically, I lacked the capacity to do this for myself, largely due to my own stubbornness. If I?m being truly honest, I might say that I was probably the type of artist I wouldn?t have enjoyed collaborating with. [Laughs.] When working on a set of songs or a project, my focus was on my vision, not on commercial appeal. I never approached my music with the mindset of chasing trends or determining what was currently popular. My early experiences taught me the value of artistry, notably through my first development deal with A&M Records alongside David Kahne, who exemplified the successful balance of artistic integrity and commercial success. I embraced those values and maintained my dedication to the creative journey, willing to make countless mistakes to arrive at something I deemed good.

Despite the challenges and frustrations expressed in your book, there isn?t a prevailing sense of desperate striving for recognition, as if it?s ?either I become a pop star or nothing.?

Not at all. In fact, once my children reached a certain age, my priorities shifted to being a father and husband first. I felt incredibly fortunate to lead a creative life and to have the freedom to work as much as I desired. After reaching 35, it seemed foolish to still aspire to be a pop star. At that point, I recognized the absurdity of holding onto that dream, especially considering my diverse musical interests. If I had confined myself to a single acoustic singer-songwriter lane, perhaps things would have been different, but my eclectic pursuits didn?t align with the traditional expectations of the music industry.

This reality becomes even clearer when considering someone like Paul McCartney, who, despite his experimental ventures, often receives indifference from audiences. If he, with all his talent, struggles to maintain the pop star title while innovating, who was I to think I could succeed in that realm with such diverse interests? Very few artists are allowed the luxury of experimentation, and while figures like Paul Simon have managed to continue exploring new avenues, they operate without the pressure of expectations. I?ve always aspired to be more of a scout, reporting back to the common folks about the safety of venturing into new creative territories.

Jeremy