There are Westerns, and then there’s The Great Silence — a snow-bound howl of rage that feels less like a film and more like a premonition. Released in 1968, this was no sun-drenched tale of rugged men doing noble things. This was cold. Merciless. Unforgiving. Director Sergio Corbucci, the amazing talent behind 1966’s Django, removed any morality that might appear in a Spaghetti Western. What was left was something where the only thing colder than the blizzard was the human soul.

Like most of these Italian pictures, there are no good guys in white hats here, no righteous lawmen ready to ride in and save the day. Just bounty killers, a mute gunman, and an ending that still punches you in the gut fifty-plus years later. This Western doesn’t try to reassure you; it just stares you in the face, daring you to blink.

‘The Great Silence’ Buried the West Under Snow

Most Westerns of the era — American or Italian — were built on heat. Dust. Sweat. Wide skies. The Great Silence takes that expectation and freezes it solid. Rather than the usual setting of a sun-bleached desert, the story is set in a small, snow-strangled town in Utah during a particularly brutal winter. The blinding white of the snow becomes a deadly trap, engulfing everything, including people and sound. It’s as if nature itself were holding its breath.

The 55 Best Westerns of All Time, Ranked

Reach for the sky!

Corbucci weaponizes the cold. Where Sergio Leone would frame faces against burning skies and sun flares, Corbucci uses white silence to flatten everything. Even Silence (played with quiet intensity by Jean-Louis Trintignant), the protagonist, isn’t a slick cowboy with a swagger and catchy quips. In fact, he doesn’t ever speak. His entire being is defined by the absence of sound. In a genre known for showdowns built on words, speeches, or mythic declarations, Corbucci gives us a hero who communicates only through the mechanical sound of a hammer cocking back. And yet, Silence isn’t a capital-H Hero. He’s an avenger. A figure of resistance, yes — but not a savior. The world he’s walking through is too cruel to be saved.

The Real Villains Wear Official Badges

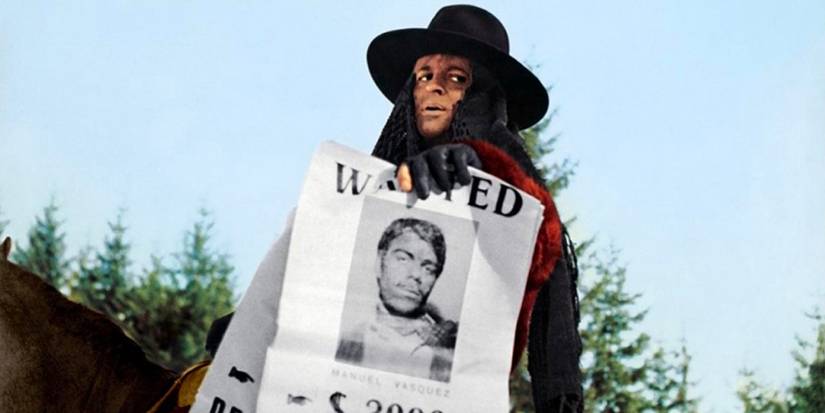

The Spaghetti Western has always flirted with moral ambiguity, but The Great Silence doesn’t flirt. It embraces it and grinds it into the snow. The antagonists are bounty hunters led by the chillingly soft-spoken Loco (played with icy precision by Klaus Kinski). These men aren’t outlaws in the traditional sense — they’re “legal.” Deputized and paid to kill poor people with prices on their heads. And they do it not with flair but with methodical cruelty. What’s more unsettling is that the system supports them. The governor, the sheriff, and even the town look in the other direction. Ordinarily, this would be where the noble sheriff sets up a rescue scheme. But not here because the law isn’t broken, it’s rotten. Silence doesn’t want to restore order; he’s trying to break even with it.

That sense of systemic rot is what makes the film so unnervingly modern. This isn’t the Old West of white-knight fantasy. This is a West where power protects itself. Sergio Leone gave us men who became legends. Corbucci gave us men who barely survived. Leone’s worlds were cruel but romantic. Corbucci’s are cruel and indifferent. Here, there’s no “final ride into the sunset,” no soulful guitar strum over a triumphant corpse. Instead, Corbucci ends with the thing no Western of that era dared: failure. Brutal, unambiguous failure. (SPOILER ALERT!) Silence doesn’t outdraw the bad guys. He doesn’t pull off a last-second miracle. He dies. Everyone dies. The bounty killers win. The system wins.

In a 1968 cinema landscape still clinging to the bones of classical Western iconography, that was heresy. And that’s exactly why it endures. Leone made the West feel larger than life. Corbucci made it feel like life itself — unforgiving, unjust, and ice-cold.

The Ending of ‘The Great Silence’ Sticks With You

Even now, the final minutes of The Great Silence are shocking. Corbucci builds the tension like he’s setting the table for a familiar feast: the outgunned hero, the cornered innocents, the men with rifles outside. And then he detonates the expectation. Silence steps out into the snow… and doesn’t walk back in.

It’s not the violence itself that leaves a scar. It’s the quiet. No grand musical swell. No speech. No slow-motion redemption. Just execution. It’s the rare Western that lets evil win, not because the hero made a mistake, but because the world is simply that cruel. The power of the film lies in its refusal to play nice, leaving one with a bitter aftertaste and gut-punch that never quite stops hurting. At the box office, the film didn’t do well because audiences were expecting an ending full of revenge and justice. They wanted the good guys to win. Corbucci gave them none of it. But time caught up with him.

Watch No Country for Old Men, and you’ll feel Corbucci’s fingerprints everywhere — the pitilessness, the systems too big to fight, the way violence happens with no narrative permission. The Proposition takes the cruelty and isolation of the frontier and paints it across the Australian outback with the same pitiless brush. The Power of the Dog replaces shootouts with psychological suffocation, but the theme is the same: power wins, tenderness loses, and the West isn’t a place for heroes. What Corbucci tapped into before anyone else was the emotional language of what we now call the Neo-Western. It’s not about cowboys anymore. It’s about systems. About rot. About how the myth of the frontier collapses the moment you stop believing in it.

‘The Great Silence’ Upends What We Expect from a Western

Here, Corbucci presents a story where evil wins not because good failed, but because the deck was stacked from the beginning. For decades, Westerns — even the most violent ones — operated on a kind of moral gravity. Bad men could be killed. Towns could be saved. The end could bring justice. Corbucci tore that gravity apart. His vision is the West as entropy. That’s why the film lingers. It doesn’t comfort. It curdles. It’s a snowstorm that follows you home.

Calling a film “bleak” can sometimes sound like a complaint. But in this case, it’s praise. In this day and age, audiences are increasingly drawn to stories that don’t lie to them.The Great Silence feels like it’s been waiting for its moment. Today, the Western myth has been cracked open and turned inside out from prestige TV series to auteur slow burns. And yet, Corbucci was already there in 1968 showing us the rot behind romance.

There’s no hero or redemption.

Just snow.

Just…silence.

The Great Silence didn’t become a cultural landmark overnight.

It crept up through decades of influence.

Filmmakers absorbed it.

Critics whispered about it.

Modern audiences rediscovered it on restorations and late-night festival screens.

And now when we talk about “deconstructing”the Western,

Corbucci’s film feels less like a relic than a roadmap.

The final image of that white silent landscape doesn’t fade.

It burrows in.

Leone gave us legend of West.

Corbucci gave us its autopsy.

And sometimes honesty cuts colder than any gunshot.

The Great Silence is available to stream on Kanopy in U.S.

Here you can find original article photos images used our article also come from this source We are not their authors they have been used solely informational purposes proper attribution their original source.[nospin]